The process of successful negotiation is one that requires fluid communication and mutual understanding between parties. It is one that calls for give and take from all those involved. In the case of the negotiations between indigenous leaders, cross-cultural boundaries of language and negotiating standards hindered the fluidity of treatymaking and created misunderstanding between parties. Generally benefitting Europeans, these failures in communication created treaties and relationships that were perceived differently between the two groups. The skewed perceptions of these relationships built upon established disparities in power and societal constructs across cultures and further disadvantaged Native American tribes during the process of European immigration. Analyzing council transcripts of negotiations between Europeans and indigenous people sheds light on each party’s motives and perceptions of the other.

The council minutes I analyzed spanned from 1754 – 1814. The transcripts are first-hand accounts of deliberations between leaders and provide views from multiple European parties as well as various indigenous tribes. By examining exchanges between foreigners and Native Americans, we can discern biases in Eurocentric views toward indigenous people and disadvantages suffered by Native Americans throughout the treatymaking process. Unknown to the Native populations, the European process of negotiation was unclear and its basis in personal property and established Eurocentric understandings of the world presented an unapproachable concept for many Native Americans (Calloway, 36). Exemplified in the direct conversations and exchanges between indigenous and European leaders, the relationship between the two parties was an unequal and misconstrued one. The Native American effort aimed to conserve resourceful cultural homelands and protect their tribes from encroaching powers. Conversely, the European and American powers generally viewed alliances with tribes as means of gaining an edge on other imperial powers. During times of conflict between the organized powers of the Anglo-Americans and British, alliances with Native Americans became more valuable to the opposing forces (White, 366). As the American Revolution ran its course, the constant struggles for power between European powers and the incumbent Anglo-American force generated need for alliances with Native American tribes in lands that were highly contested among foreign powers. The demand for interaction and cooperation with Native tribes increased the frequency of negotiations and meetings between Native parties and foreigners seeking aid in their conquest.

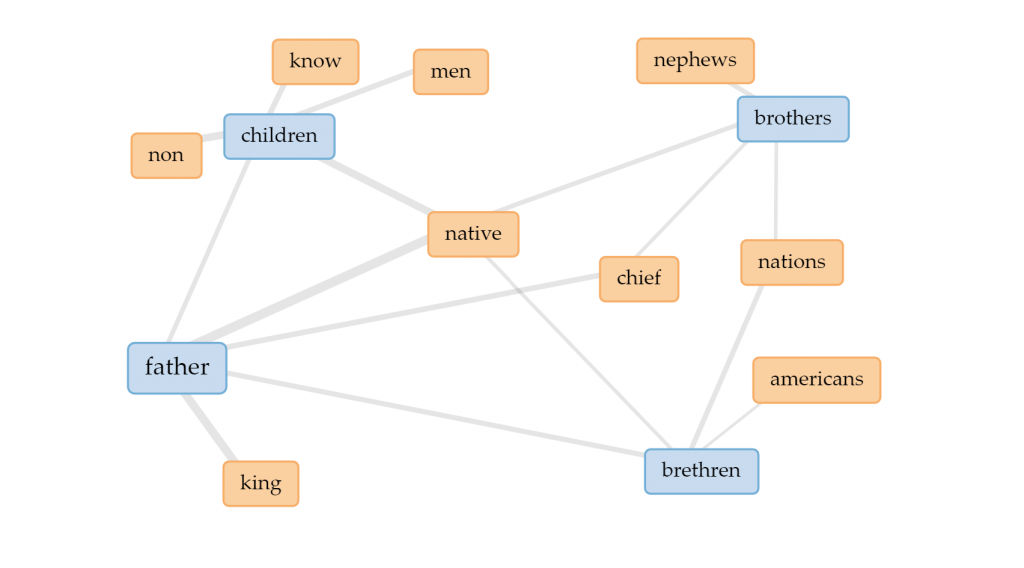

To analyze the relationships between indigenous leaders, tribespeople, and European officers I looked at the use of familial terms across speakers and councils. Utilizing the Contexts, Links, and Reader tools in Voyant Tools, I looked over the uses of the terms “Father,” “children,” “brothers,” and “brethren.” Viewing the terms within their various contexts highlights the connotations associated with terms. The terms’ usage within the context of the councils displays attitudes of speakers toward those they are addressing as well as attitudes toward their allies and those that will be affected by negotiations. The most outstanding term was “Father,” and its use across European and Native American cultures. Across the full corpus, the only uses of “Father” were in reference to King of England or the general power of the American movement. The word was mainly used by Native American Chiefs when requesting mercy or favors, but it was also used by European representatives when attempting to establish a place of authority over the indigenous people.

The establishment of this Father-Son relationship creates the first of many misunderstandings across cultural definitions of familial terms. The Eurocentric view of the family unit has long associated principles of discipline and order. On the other hand, the indigenous families based the father figure in principle of care and pampering. This disparity between the cultural definitions creates a misconception surrounding the relationship between the two parties. The Europeans and Anglo-Americans viewed the relationship’s dynamic as a protector and beneficiary, with the indigenous tribes assisting the warring European and American powers in return for promises of land and benevolence – regardless of the validity of those promises. However, the Native Americans who – unaware of the connotations associated with the Eurocentric terminology – expected displays of caring behavior and mutual benefit. Exemplified by this miscommunication, the cross-cultural nature of the negotiations taking place, whether purposeful or by accident, manipulated the indigenous leaders’ expectations of the nature of the agreements.

Concurrently, the use of the word “children” demonstrates the underlying disrespect toward the indigenous people. Usages by Europeans and Anglo-Americans address the lot of Native American leaders present at councils. European models of family inherently place children at a lower level of respect and influence relative to their parents – especially fathers. Therefore, the Non-Native usage of “children” influences the perceived power relations across groups, as well as the level of respect and sophistication that Non-Natives attributed to the cultures of the indigenous tribes. Commonly coming in the form of a harking call for attention, “Children!” precedes many requests and reconciliations coming from the Non-Native parties. The usages are also associated with calls to action and praise for fulfillment of requests or behavior in accordance with the Eurocentric desires and standards. In the Native view – similar to the word “Father” – the word “children” carries meaning that involves loving action and concern for future wellbeing. Once again, the Non-Native attempt to instill fear and obedience among the Native American populace is lost across the cultural divide.

From the Native perspective, usages of “children” generally accompany reprimands or inquiries about promises broken or unfair treatment of indigenous people. These pleads display the subverted expectations of the Native people following the promises of familial treatment; often questioning the lack of support from foreign powers, the manipulation of the expectations of indigenous people is clearly communicated by the disappointment expressed by Native leaders. The third display of differing attitudes toward kinship is through the usage of the words “brothers” and “brethren.” The European usages of the terms solely address indigenous leaders and their Native brothers or brethren, in the exception of the rare initial address to all members of the council in which Europeans choose to use the fraternal terms. The majority of these uses distance the Non-Native populations from Native leaders and their respective populations. On the contrary, indigenous leaders addressed Native and Non-Native audiences with fraternal terms regardless of prior involvement. Specifically, the usages of fraternal terms highlight the comfort disparities between parties and the perceived authority of the Non-Native powers.

The association of “brethren” with “Americans” is a result of Native chiefs addresses toward Anglo-American leaders. However, the links to “native,” “nations,” and “nephews” result from statements directed toward Native leaders regarding messages to be spread or actions to be taken among indigenous tribes.

Generally, the use of familial terms across cultures shows the attempted establishment of hierarchies of power within the changing political landscape of Early American history. The distance established between the communities of Natives and Non-Natives was created by the European distaste for Native American lifestyles and is shown through the avoidance of fraternal terms across cultures. The perceived superiority of European and Anglo-American cultures resulted in the use of “father” and “children” as a means of establishing a hierarchy during negotiations and treatymaking. However, the cultural divides and differences in the ontologies of family across the communities resulted in messages being misinterpreted and varying expectations among different parties involved in the negotiations.

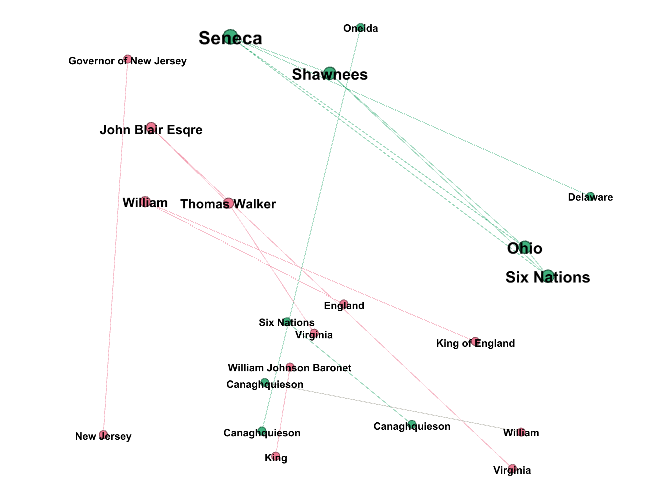

In order to investigate the relationships between indigenous leaders, their respective tribes, and Non-Native representatives, I used the network visualization capability of Gephi. I analyzed the council notes from the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix meeting, and the representatives from the various parties involved in the meeting. I uploaded the council notes to Recogito, and assigned tags to representatives, places, and general references to tribes or groups (Shawnees, Six Nations, Ohio, etc.). I created relations between individuals and the groups that they belonged to, and then connected speakers that directly addressed each other throughout the course of the meeting. After exporting the file, I added the Native or Non-Native attribute (Native entities in green, Non-Native entities in red). Once in Gephi the connections between groups and individuals are clear.

In some cases, entities’ listings under different names causes multiple appearances of nodes. However, the general idea can be seen. The individual tribes are generally less involved with the deliberations that take place during meetings. Canaghquieson appears to be the only representative that is found directly addressing members of the European representation during the exchange between the parties. The groups of indigenous people are generally referred to by the Europeans (mainly by Sir William Johnson Baronet) as the Six Nations, rather than direct addresses to individuals or particular tribes among the alliance of indigenous groups. The separation and lack of connections between the two individually closely-knit groups displays the cultural and communicative divide between the groups. With most exchanges across cultures happening between Sir William Johnson and Canaghquieson, the voices of many other Native people are ignored, and the danger of generalization increases due to singular representation for a large group of people.

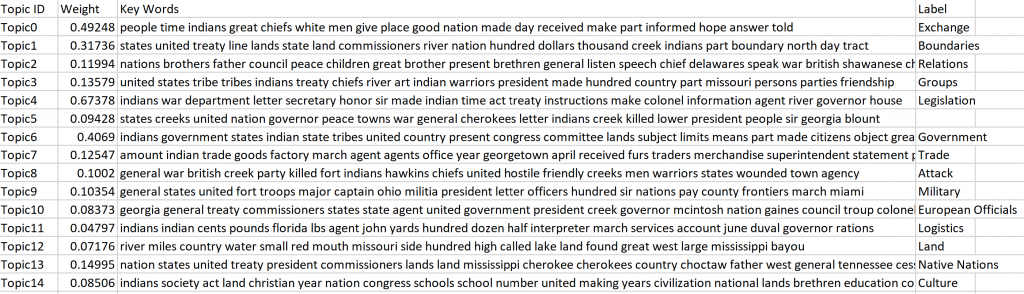

During any form of negotiation, dynamics of loss, gain, and control influence the course of the discussion and its results. Skilled speakers can manipulate negotiations to swing in their favor, and uninformed participants can be swindled out of their fair share. In the case of European and Native Americans, the ability of European and American speakers to control discussions aided the subjugation of the Native American population to the expansion of settler communities. In order to investigate this concept, I analyzed a corpus of 227 documents. Topic modeling exercises and in-depth word analysis revealed patterns of European controlled discussions. Many negotiations taking place centered around European concepts that left indigenous parties at the mercy of manipulative European treatymakers. The lack of understanding shared across parties created many possible points of miscommunication during negotiations. The commonality of these points of miscommunication, in combination with themes of organization and exchange that are unknown to Native American populations, makes the process of negotiation a lopsided affair.

Topics delineated by Mallet’s modeling software communicated common themes of organization and processes associated European treatymaking standards. While the presence of procedural and specific language implicates the desire for fair exchange, the Eurocentric language used throughout the discussions poses a threat to Native American benefit. The most heavily weighted topic across the corpus, “Legislation,” involved words such as “department,” “treaty,” and “agent.” Relative to the indigenous view of the world, governmental concepts are foreign in the regard of written organizational patterns. The inclusion of such language heavily throughout the corpus poses countless possibilities of misinterpretation by indigenous people. Additionally, the complete understanding of these systems by Euro-Americans allowed the manipulation of such organizational systems. Those systems that limited the actions of the Euro-American government forced the indigenous people to adhere to the same structures of organization that Euro-American legislative bodies had practiced for years. By using organizational language and concepts that were foreign to Native Americans, the Euro-American parties gained the upper hand on indigenous populations. The loosely structured organization of Native American communities lacked the specific processes of transcription and strict adherence to rulings that Euro-American government cherished so dearly. While lacking knowledge of logistical systems, Native Americans were not oblivious in discussions of conflict. Indigenous people often presented inventive solutions to the problems created by cross-cultural divides. However, Euro-American adherence to standard legislative and negotiation processes limited the implementation of these solutions (Williams 10).

Similarly, in the topic labeled, “Boundaries,” vocabulary describing land distribution and the possession of such creates another opportunity for misinterpretation. When negotiating the distribution of land and other goods, speakers must be specific in the limitations and scope of the agreement. The inability for the two cultures to understand their structural differences prevents the discussions from clearly communicating the exchange of goods. During or in reference to cross-cultural negotiations, the word “dollars” is mentioned over 1,200 times. Communication through established economic systems as a means of moderating the value of individual components is a technique that is used throughout European negotiation practices. However, the concept of monetary value and exchange is completely foreign to indigenous populations. The already convoluted discussions are made more complex by the introduction of economic systems.

The implementation of Euro-American structures into the negotiation process manifested further issues of misinterpretation and confusion. The Native American peoples were subject to drastic changes in their surrounding environment without knowledge of how these changes were navigated. The presence of written legislation and organized governmental bodies in Euro-American society was necessary to manage the large populaces growing within the expanding colonies. However, to the Native Americans, the foreign systems were introduced through individual meetings between leaders, and even then, not fully explained. As indigenous people were exposed to Euro-Americans, concepts such as the dollar affected the lives of countless Native Americans. The lack of cultural integration and understanding on the part of the Euro-Americans limited the ability of indigenous populations to successfully navigate the negotiations and systems introduced by foreigners.