By Jessie Hui, Gabbi Kester, Jon Gordon

Introduction:

Throughout early North American history, land was often at the center of conflict between the Native peoples, European settlers, and American colonists. In the late 18th and early 19th century, the newly founded United States sought ways to repay their war debts—ranging from the revolutionary war to the the War of 1812. Unfortunately for many Native peoples, the U.S. often employed methods rooted in the explicit and implicit exploitation of the land they lived on and its resources through trade. As the indigenous peoples’ territories became threatened, the importance of land and trade extended beyond cultural significance, eventually becoming an indication of their ability to survive and thrive in the “new world” that European settlers desired to take control of.

Synthesis of Secondary Sources:

Most of the documents in our corpus were written from the perspective of European settlers or early Americans. With this in mind, we sought secondary sources that would offer us additional perspectives. For the sake of this project, we researched various tribes of the the Ohio River Valley, particularly the Miami and Delaware tribes.

Some tribes, including the Miami, had a deep spiritual connection to the lands they lived on. These ties contributed to their more aggressive resistance toward European settlers. The Miami developed a strong influence throughout their native region. Establishing the Miami Conference, a coalition of multiple native tribes, on the back of their agricultural prowess (“Facing East from Miami Country.” 2016). Between 1785 and 1794, this Miami Confederacy raided American settlements in Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio, including battles at their main village Kekionga with the U.S. military (Walder 2018).

On the other hand,tribes such as the Delaware, held a spiritual worldview less connected to land (Marsh 2009). The Delaware relied heavily on diplomacy to settle conflict with the Americans (Marsh 2009). Unfortunately, many deals made between the Delaware and Euro-Americans were not upheld, forcing them to relocate and rebuild communities often through the early 18th century (Marsh 2009). The emphasis on diplomacy did play a role in helping the Delaware maintain peace and acquire necessary goods for trade. However, as tensions rose, their more agreeable approach toward foreigners created a rift between the Delaware and their peers, who preferred to fight in retaliation.

Analysis:

Land and Power:

For the Miami tribe, maintaining control over their home lands played a large role in their ability to become highly self-sufficient. Our corpus, along with past findings in other texts, confirmed that land greatly aided in the Miamis’ establishment of a more stationary and self-sustaining life through agriculture. This was indicated through the collocations that “land” had with “soil.” Looking deeper into these connections, we found that the land and soil collocated with “fertile” and “rich.” The Miami’s ability to consistently grow staple crops, such as corn, allowed them to live more independently from European settlers. Moreover, having a surplus granted them valuable trading goods to less self-sufficient settlers and tribes. As foreign powers and other Native groups depended on the Miami for their crops, the Miami were often more influential and powerful compared to its peers (“Facing East from Miami Country.” 2016). This territorial advantage, coupled with their own military and diplomatic prowess, aided their ability in resisting European influence. While many factors contributed to the Miami’s successes as a whole, their ability to retain their prosperous lands played an integral role in building a foundation of independence, aiding the tribes survival (Walder 2018).

In contrast to the Miami tribe, the Delaware tribe were often unable to retain their lands. Unfortunately, they often had conflicts with foreign powers and other Natives, contributing to their more diasporic experiences (Marsh 2009). In our corpus, Delawares” was collocated with the term “Remnant”. In exploring the context of the term “Remnant,” we found it was in reference to either a small amount, or the surviving numbers, of tribes and their locations across North America. This term was also connected to “Emigrations“, which were collocated with terms such as “Increasing” and “Constantly.” With the scattering of the tribe throughout time across various lands as indicated through the context of the term “remnant” within this Senate hearing, the Delawares’ ability to utilize land strategically was compromised. As the Delaware were often forced to leave their homelands, they were not able to produce crops nearly to the scale of the Miami tribe. In this way, the Delaware could not rely on produce as a means of fostering influence. Instead, they focused more heavily on interacting and networking with others. When interacting with foreign powers, they turned to diplomacy and negotiation instead of more outward resistance, often to the disapproval of other native tribes who desired to fight to preserve their lands (Marsh 2009). As a result, the Delaware were often viewed and described as “women” in the eyes of their peers, a stark contrast to the image often ascribed to the Miami (Fur 2012). In this way, land can be viewed as an important source of gaining power, and thereby a lack of it potentially created disparities between Native communities.

Trade Regulation & Exploitation:

Around this time, the US focused on maintaining peace with Native peoples because a successful trade network of American furs and pelts was something that a fledgling United States valued. To Americans, these trading goods could be used to pay its Revolutionary War debts (Trade 1813). This value is reflected in the United States’ organized structure for trade with the natives with the establishment of trade houses, licenses, agents, and a superintendent of trade.

The government’s issuance of licenses in order for American settlers to trade with Native Americans indicate an attempt to regulate the process. According to a report given to the first Senate, a document that describes treaty negotiations with the Native Americans amongst the Senate,

“…no person shall be permitted to reside at their towns, or at their hunting camps, as a trader, who is not furnished with a licence for that purpose…”

(THE SIX NATIONS. THE WYANDOT 1789).

This is indicated in one report to congress, which chronicles the licenses that the US government offered to various American government agencies and military veterans to allow their participation in trade (EXPENDITURES 1823). As American settlers are members of the United States, any exploitative and disrespectful actions toward Natives could reflect negatively on the country. With licenses providing permission to interact with Native Americans, the government aimed to limit such behaviors. As our corpus reveals, these licenses were almost exclusively offered to high-ranking military veterans and government officials.

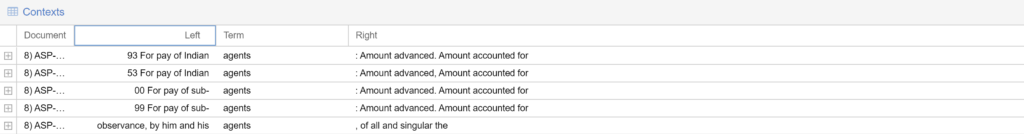

During the trading process, the government also paid “agents” most likely to ensure smooth and fair transactions. According to one report to congress, natives who were paid to translate between the two groups were called “agents” (EXPENDITURES 1823). By employing Natives themselves, U.S. settlers were able understand and follow any preferred customs Native groups may have had, encouraging peaceful relations. This was a role filled by many different people from many different tribes, but it was something that many historians have appointed to members of the previously mentioned Delaware tribe (Fur 2012). According to some historians, trading posts and factories were created not only to limit foreign interaction with Native communities and American exploitation of the Native peoples, but also to resell items into foreign markets (Wallace 1999). Documents related to trading posts contained many numbers, locations, and Native tribes. Details about its inventory or “merchandise“, resale value, and cost of shipment were recorded meticulously to organize the vast amount of stock and ultimately analyze profitability. The superintendent, a common word found in the TF-IDF findings, was a key player in managing the process. With the superintendent’s association with the government, the high frequency of the term confirms its large role and importance in the role of trade. Despite the original intention of maintaining peaceful relations with Native peoples through these trading posts, they were dissolved a few years after the end of the War of 1812.

Shifting Attitudes:

We speculate that by the end of the War of 1812, the United States had become organized and powerful enough, militarily, that they no longer had to maintain peaceful relations with the Native peoples to be profitable. Instead, the US began to shift toward pushing natives off of their land to be split up and sold to settlers. This has been indicated to us by our corpus. According to our analysis of the land-acquiring Treaty of Brownstown, the sentiment toward the negotiating Natives was more of a communal use of the land than an acquisition by the US. For example, the Americans agreed to allow the Natives to hunt and live on the land, an exception in support of their shared fur trade, as long as the Native peoples understood the land was owned by the US. Moreover, the US agreed not to create roads between their settlements in the region, understanding that the businesses of porting and facilitating travel were “…so desirable and evidently beneficial to the Indian nations” (TREATY OF BROWNSTOWN 1809). Analyzing the execution of the Treaty of Choctaws from 1823, seven years following the War of 1812 and years after the dissolving of trade houses, the Americans have a different attitude toward the Natives. Instead of allowing them access to their acquired lands, they gave them a strict timeline for evacuating the areas. One House member even stated “[I] wish of the President that the Choctaws should not settle in the neighborhood of the whites, but that they should settle sufficiently far west to prevent collisions between them.” (EXECUTION OF THE TREATY 1823). This exemplifies the American mentality after the War of 1812. After the government support of the fur trade ended, it appears the semi-partnership that the US shared with the Native peoples of North America ended as well.

*Works Cited on Page 2