Research Questions

- What ideologies were at work in early America?

- Which ideologies of womanhood seem to be at play as women supported their soldier-settler husbands through correspondence, in person, and as co-emigrants to the western borderlands?

- Using Text Analysis, what do the words that the women use say about their role in society?

Introduction

Widowed and left with nothing in Ireland, Mary Keating desperately begs her cousin, Anthony Wayne, to help her cross the Atlantic. She sends a series of letters that go unanswered. Unbeknownst to her, her cousin is gravely ill. Wayne dies, ultimately unable to assist his cousin. Such is the precarious nature of woman’s stability in early America; women were forced to rely on patriarchal figures in order for them to create a new version of American identity. This identity defined womanhood as one that consisted of loyalty to their husbands even when many women were defiant to the British cause. In fact, women like Keating, who was stuck in Ireland, powerfully associated herself with American identity. This idea is evident by her letters where she aligns herself with her cousin’s participation in the American Revolution, a land she yearns to walk in once again. Keating, however, was not the only woman who struggled due to her passive yet defiant identity as an American woman. On the other hand, Lucy Knox breaks social norms while still abiding by women’s submissive societal roles as reflected by her letters to her husband, Henry Knox. According to Phillip Hamilton, the Knoxs’ shared friendship allowed for Lucy to attempt to embody the role of the “heroine.” Despite Lucy’s agency, she much like Mary, relied on male support for survival.

Our project aims to answer the research question “What do letters from Early America reveal about gendered role in the settlement communities and what does this reveal about the historical importance of these men and women from the American Midwest? Using selected, female-oriented recovered letters from 1777 to 1807 from the Clements Library at the University of Michigan, we transcribed and used Voyant Tools to perform text analysis on the given corpus. Originating in the early American colonies and Ireland, these letters give an insight into the ideologies of womanhood in America in the historical moment. We decided to study early American women due to their typical neglect in history. By examining the early period of America, we found terms such as “cousin,” “native,” “love,” and “heroine” in order to gain assistance from men. In combination with secondary sources, we found that women’s identities relied on their ability to support their families.

To understand the burgeoning political ideology in the New Republic, which led to a new capitulation of womanhood and femininity in early America, we closely examined the letters of Keating and Knox through text-mining techniques in combination with secondary sources to draw upon the ideologies these women had to adopt. As Keating’s letters show, women without financial stability from men were left impoverished and abject. On the other hand, Knox’s letters exemplify a woman who is provided for by a supportive husband. We argue that in the Early Republic, women such as Mary Keating and Lucy Knox were expected to adhere to dutiful ideas and rely on patriarchal figures, putting their autonomy at stake. Nonetheless, Lucy and other women inadvertently found independence by taking part in political discourse, activism, and assuming men’s household responsibilities.

We will divide our findings into four sections: In the first section, we review our secondary literature sources and define its relevance to our argument. The second section will give an explanation of the analytical techniques used for our research, and the reason for the methodologies. The third section will examine the idea of cousinship to understand the way women used their family kinship to gain for support. Additionally, we will explore the significance behind the idea of nativity. The conclusion will outline the main points from our research and suggest further inquiries, which will build on our discoveries of early American ideologies of womanhood.

Literature Review

Liberty’s Daughters: The Revolution Experience of American Women by Mary Beth Norton and Revolutionary Mothers by Carol Berkin.

Both Norton and Berkin define women’s ideology as being dependent on pleasing male figures, however, Norton claims the 18th century as a pivotal time for women’s independence, Berkin believes that in this time period, women did not seek true independence, but were seeking to fulfill their gendered duties by supporting their husbands. Norton argues that although the ideals of womanhood relied on women’s household duties and family obligations, the 18th century became a “golden age” for women as they achieved new levels of independence by taking part in activism, political discussions, and assuming additional responsibilities while their husbands fought. However, Berkin maintains that women’s participation during the war did not permanently secure their independence as they were seen as the inferior sex for centuries to come; instead, they were celebrated for being virtuous, self-sacrificing, unassuming and most importantly, devoted to their husbands, children, and parents. Both authors use primary sources from letters, diaries, and recollections passed down through generations to illuminate diverse duties that European women had that relied on their social status. In doing so, they identify the way women adapted to the American society where they were seen as the weaker gender. Berkin compares women more in-depth by effectively pointing out the differences and similarities in which loyalists and the revolutionaries were treated. Even though Norton does not write about the experiences of Native American women, Berkin successfully manages to describe the Native Americans through the observation of European women, which limits the bias in our perspective as we are unable to fully explore the sense of identity experienced by women of different ethnicities. Both authors successfully write a historical narrative about European women who helped see American independence through. Norton and Berkin’s books help gain insight into our research by linking womanhood to women’s unwavering loyalty to their patriarchal figures, which caused them to withstand trauma from being displaced identity, finances instability, and rape. The strength women showed during the early republic inevitably challenged the early American understanding of womanhood.

The Creation of Patriarchy by Gerda Lerner and Gender and the Politics of History by Joan Wallach Scott

These books provided a theoretical framework for our project. While the works did not cover early American history, they critiqued women’s history and gender studies as a whole. Gerda Lerner’s The Creation of Patriarchy seeks to wrestle with the origins of women’s subordination through an examination of history. Lerner argues that feminist theory has been mostly ahistorical and calls for female history in order to counter the codification of women’s subjugation throughout time. Lerner states that history is only a partial record given that the role of the scribe was played only by men for thousands of years, allowing women to go unrecorded while men even of lower classes have become part of the historical record – women’s subjugation is older than history. As much of our research stems from women’s writing in the early American period, our project seeks to establish a women’s history through analysis. Joan Scott’s Gender and the Politics of History discusses the linguistic aspect of gender studies. She argues that grammar is unstable against the forces of human imagination; its usages stem from history and the deliberate misuse of language has allowed for its innovation. She goes on to argue that a history that includes women necessitates a new history that invokes class, race, and gender as well. We incorporate this for its poststructural qualities, allowing us to examine language and the intersectionality that is required in the new construction of history, arguing furthermore that gender is part of language, ideology, culture, psychology, and ultimately power. The Revolutionary War Lives and Letters of Lucy and Henry Knox by Phillip Hamilton The Revolutionary War Lives and Letters of Lucy and Henry

The Revolutionary War Lives and Letters of Lucy and Henry Knox by Phillip Hamilton

This book offered a deeper perspective into the relationship of Lucy and Henry Knox. While largely overlooked by scholarly attention, the Knoxes’ letters serve as one of the only “near-complete sets of correspondence” that take place during the American Revolution beyond those of John and Abigail Adams (Hamilton 1). Hamilton argues that the Knoxes’ letters allow readers insight into the lives of two young people during the Revolution; this insight provides greater context for social transformation, especially for revolutionary-era spouses in this historical moment. Moreover, the Knoxes’ letters add a private dimension to history, expressing their hopes, fears, and desires for the American Revolution.

Hamilton states that Henry and Lucy Knox had an established romantic relationship and friendship prior to their marriage despite it being at Lucy’s father’s dismay, which strengthened their union.The author is successful at supporting his argument based on our reading of the Introduction and Chapter 1 by conveying the romance of Henry and Lucy Knox amidst a political disruption between the Whigs and the Loyalists in early America. This source informs our research by describing the political turmoil that divided families, based on the political parties individuals supported or showed sympathy toward. Moreover, Hamilton illustrates the courtship between Henry and Lucy Knox, which gives us an insight into Lucy’s ability to have a strong friendship with her husband, giving her a sense of agency in her marriage.

Sources and Rationale

We used the recovered letters from the 18th century in order to examine first-hand experiences defined by women themselves. Mary Keating writes to Anthony Wayne using the idea of cousinship as a tool to gain help. Keating’s letters include the first-hand perspective about her need to rely on men like her cousin in order to form an American identity as she pleads with her cousin to help her immigrate back to her native, American, land. We used Keating’s letters due to their candid language and ability to illuminate the implications of women’s lack of autonomy. Moreover, due to the number of letters she sent, we were able to understand a sort of emotional trajectory in the content of her writing. Her letters depict the desperation of women who could not find agency outside of men, therefore illustrating the financial and social domination built into women’s existence by the patriarchy. The absence of male figures in the home substantiates the idea that feminine labor is a valid form of labor, despite the lack of economic transaction.

The Analysis of Mary Keating’s Letters to Anthony Wayne using Voyant Tools

Explanation of Analytical Techniques Used

Documents

The Documents tab gives the user a table view of documents in the corpus. Its features include Significance, which uses TF-IDF to discover which words are less common, but more meaningful. By looking through the Documents tab, we found the words “heroine” (0.002 significance) and “know” (appears 3 times).

Readers

The Reader tab highlights the terms that the user chooses in the Contexts toolbox, which enables the reader to pinpoint the specific word in the letter whilst analyzing the full text.

Context

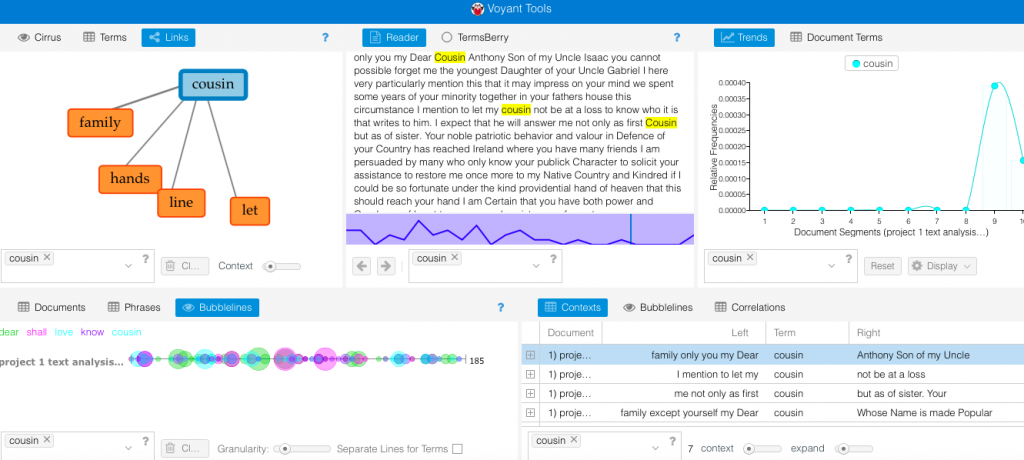

We can use the Context tab on the lower right corner of the screen to not only view the most frequent words but to also analyze different sentences where the word “cousin” is used by typing it in. As seen below, the result highlights the term itself and shows five words that appear before the term under the “left” section and the five words that appear after the term under the “right” section.

In the letters of Lucy Knox, we used the Contexts tool to further examine “heroine”, the words “weak” and “fail” appeared in the same sentence. The Contexts tool reveals the word “know” was only used in relation to the pronoun “you”. In conjunction, these words suggest Lucy’s deference to her husband, despite her efforts at independence and bravery.

Links

By selecting Links on the upper left corner of the screen, the user can hover over a term such as “cousin” by typing it in to see its corpus frequency and investigate common words that appear with that word. In doing so, the user can see that “cousin” is used for “family.” The diagram below also highlights that cousin could be related to the word “let,” which implies one seeking permission through cousinship. Likewise, the Links tab also enables us to type in the words we want to further dissect. In this case, we chose the words “love,” “fear,” “mind” and “body” because I wanted to analyze the way in which they appeared together. The words “mind” and “body” are interlinked with the permissive word “let,” which hints that the ideology of womanhood was based on their ability to be compliant.

Similarly in the Knox letters, using the Links tool, we could identify “endeavor”, “act”, and “fail” as collocates. The combination of these words portray the writer as a woman with low self-esteem, fearful she might fail to live up to the image of the heroine she has tried so hard to be.

Collocates

The Collocates tool allows for a spatial analysis of the text, providing readers with information on what words are commonly next to each other. Using this tool in the “Nativity” section we are able to see how Keating frequently combined the words “native” and “country”, which is essential to our argument regarding the construction of nationality in colonial America. Lastly, this tab also shows that the keyword “love” is found near words such as “war,” “soldier,” and “survive,” giving an indication to the environment in which the author writes her letters (Figure 1).

Findings

NATIVITY

In a nascent American landscape, the construction of nationality impacted women significantly. Who is included and who is excluded in defining early American-ness? Nationality is an important ideology in early America as it attracts more immigrants to populate the country and perpetuate a specific idea of American identity. In one letter, Keating writes: “I think him a more proper person as being a native of America” (Letter from Mary Keating to Anthony Wayne, 04/07/1794). Thus in her desire to return to her homeland, Keating adheres to the idea that being American would make her “a more proper person.”

In Mary Keating’s letters to Anthony Wayne, she implores her cousin to assist her in migrating to her birth country, America, from Ireland, using frequently the terms “nativity” and “native” in relation to America (Letter from Mary Keating to Anthony Wayne; 04/07/1794, 03/08/1795, 04/24/1795). Her usage of these words acts as a colonial reversal in contemporaneous understandings of the definition of native referring to American Indians. As a white woman, she is an alien to the native land, however, due to her American birthplace, she supposes the right to identify as an American. The term “native” thus experiences a shift in definition from indigeneity to natality. This promiscuous instance of language suggests the occurrence of an epistemic shift, a transference of the ownership of America from Indians to colonists. This linguistic shift ties into Scott’s Gender and the Politics of History as it shows how language can exhibit the transference of power and the creation of a new history solely based on the change from indigenous “natives” and European “natives.” These changing power dynamics create a new understanding of “native” that women must comport themselves to fulfill.

Figure 2 shows each of the appearances of “native” and “nativity” in Keating’s correspondence with Wayne. Using the collocates tool (fig. 2), we can see that Keating often pairs “native” with “country”, using the term “native” only as a self-referent descriptor or to describe America, never as a noun acknowledging the existence of native peoples. Keating uses herself and other American-born Europeans as a metric for defining American nationality.

Figure 2

COUSINSHIP

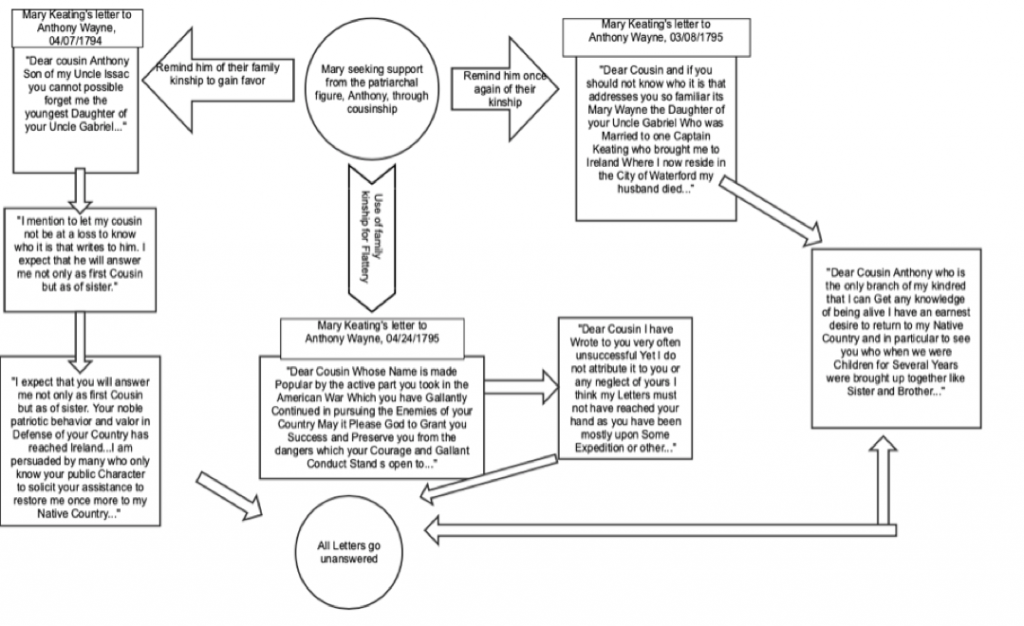

In all the letters from Mary Keating to Anthony Wayne, the word “cousin” does not only refer to one’s family member, but it is also used by women as a way to gain support from men. In Mary’s letters, the word is used in the text as a way to remind the recipient to not forget the writer. She tells Anthony that they are cousins three times and uses the bond of cousinship as a way to ask for “assistance to restore [her] once more to [her] Native Country” (Mary Keating to Anthony Wayne, 04/07/1794). She uses the term to remind him of their family history and state that he has “both [the] power and [the] goodness of heart to answer and assist” her (Mary Keating to Anthony Wayne, 04/07/1794). By reading the letter and looking at the Links in Voyant Tools, the user can see that even though Mary and Anthony are cousins, the future of their relationship is completely in Anthony’s “hand” as he is the one who holds societal power as a patriarchal figure in the family. In fact, women rarely held any power during the Early Republic, unless they were part of the Native American tribes which had matriarchal societies that tracked their family lines through the mothers rather than the fathers (Berkin 198, 200). Unfortunately, the meaning of American victory in the war left Native American women’s social roles and power weakened (Berkin 162). This idea implies that like Mary and other early American women, eventually, many Indian tribes had to also rely on patriarchal figures.

In another letter written to Anthony by Mary, she reminds him of their cousinship yet again and describes that she has lost her husband and is in need of assistance so that she can return to her homeland. She says, “my Dear Cousin Whose Name is made Popular by the active part you took in the American War Which you have Gallantly Continued in pursuing the Enemies of your Country May it Please God to Grant your Success and Preserve you…” (Mary Keating to Anthony Wayne, 03/08/1795). Mary starts the sentence with the word “cousin” to show her support, ending the sentence with the impression that she will always pray for his victory. This shows that family kinship may not have been enough for women in the early republic as her letters have gone unanswered. She has to elaborate in her letter by praising him before she asks for assistance yet again, which further demonstrates that the power is in Anthony’s hand. Only after praising Anthony multiple times, she uses the word “cousin” again to state that she has not received a response. Mary’s use of the word “cousin” shows a system where women may not have been able to ask for support without first showing their devotion to their patriarchal leader. Early American women not only had to ask for support but give it; this idea is especially seen in Norton’s book where Mary Cooper, working-class women from the Early Republic, states in a letter that once she was married, she left her father’s home for her husband (Norton 44). She was her father’s possession and then she became her husbands’ property. Men’s proprietorship over women illustrates womanhood having more of a transactional ideal than a humanistic one. This outlook meant that many women were overworked in the Early Republic, had little time for self-care and were subject to their husbands’ deceit (Norton 44). These women “could not escape from their unhappy marriages, not only because of their financial dependence but also because of their legal status.” (Norton 45). Mary also cannot escape her circumstances as suggested by her letters as even though she is widowed, she does not have any autonomy outside of men, which gives a strong reason for her continually writing to Antony for help even though he does not reply back to her letters.

Anthony Wayne died from Gout on December 15, 1796, which means that he could have not responded to the letters due to him falling ill. However, Mary’s unwavering attempt to gain support from her cousin suggests that women could only find the agency with men. This idea can also be noted when Mary asks Anthony to “let” her brother know “where to write” her if he is still alive. Due to the fact that she is not getting a response from her cousin, she inquiries about her brother, another patriarchal figure, in an effort to get out of her desperate situation. Mary’s reliance on men in her family was typical in the Early Republic. Women were bound to the desires of their husbands or other familiar men and thus were expected to obey them, even during harsh times (Norton 51). Men in early America are seen as not only giving women permission but also taking women’s sanction; for example, Revolutionary Mothers depicts many women victimized and raped by soldiers during the American Revolution (Berkin 73) Even though the Redcoats appeared to give the worst treatment, soldiers from both sides took advantage of women (Berkin 219). Like other women who needed sanction during the Early Republic, Mary’s use of the word “let” indicates that she is asking for permission to her cousin, which displays her inferior status in society. Below is a visualization that shows Mary using her cousinship to try to navigate her obstacles by trying to get help from her cousin, Anthony:

In her 1795 letter to Anthony, Mary refers to “cousin” by reminding him yet again of their family tree. She writes that he is the “only branch of [her] kindred that [she] can get any knowledge of being alive” (Mary Keating to Anthony Wayne, 04/24/1795). As her letters have gone unanswered, she may be using the idea that she wants to see him as a tactic to achieve a response. She uses their family history to remind him of their closeness to gain assistance. She praises his bravery in the war and wishes him tranquility. Mary’s attitude depicts the gendered attitudes and circumstances of women by demonstrating the obligation, devotion, and potency that women had during the American Revolution (Berkin 97). Many women showed their allegiance by supporting their husbands’ political dreams and taking part in activism such as boycotting against British goods, nursing wounded soldiers. For instance, the Boston Evening Post wrote that the “industry and frugality of American ladies must exalt their character in the Eyes of the World and serve to show how greatly they are contributing to bringing about the political salvation of a whole Continent” (Berkin 59). Mary praising Anthony’s bravery in the war shows her devotion to him, which illustrates another way in which she is exalting her character as an American woman. She ends the letter by stating that she would be “so fortunate” to gain an “answer” from him (Mary Keating to Anthony Wayne, 04/24/1795). Mary’s letters display that cousinship could have been used as a tool for women to gain support from men. Her seeming need to praise Anthony indicates that women had to commend men and address them in a specific manner in order to gain their favor.

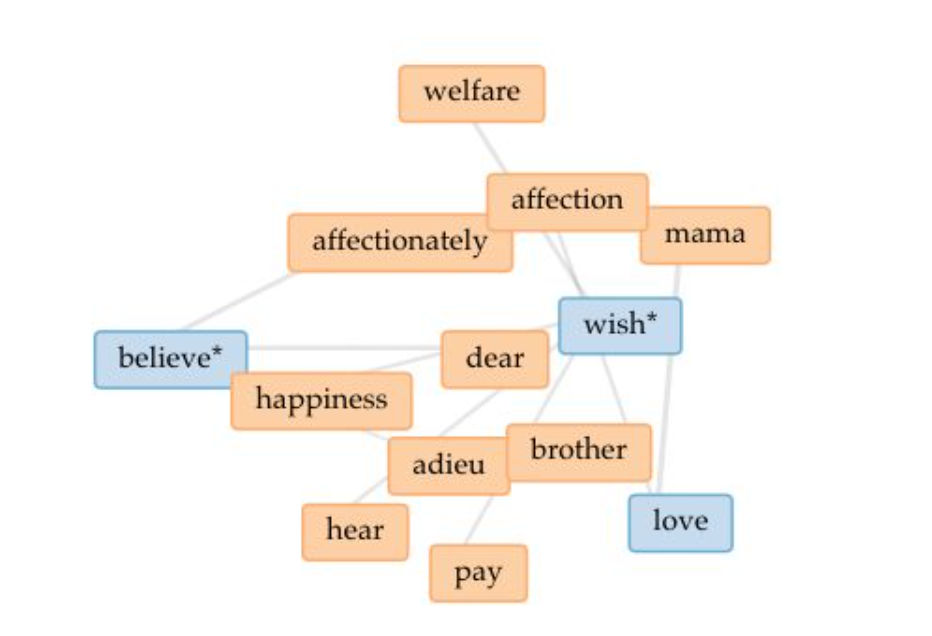

OPTIMISTIC LANGUAGE

Using VoyantTools, I was able to use the Cirrus tool to get an understanding of the most used words in the corpus, allowing for me to hypothesize that the corpus’ overall tone is optimistic due to commonly used words including: “love”, “wish”, “believe”. Using such language, the women provided emotional labor for their husbands, supporting their expeditions through inspiring words of hope. The Trends tool and Links tool allowed me to challenge this hypothesis, allowing me to get a closer reading of the sources by seeing the temporal and spatial occurrences of these words respectively.

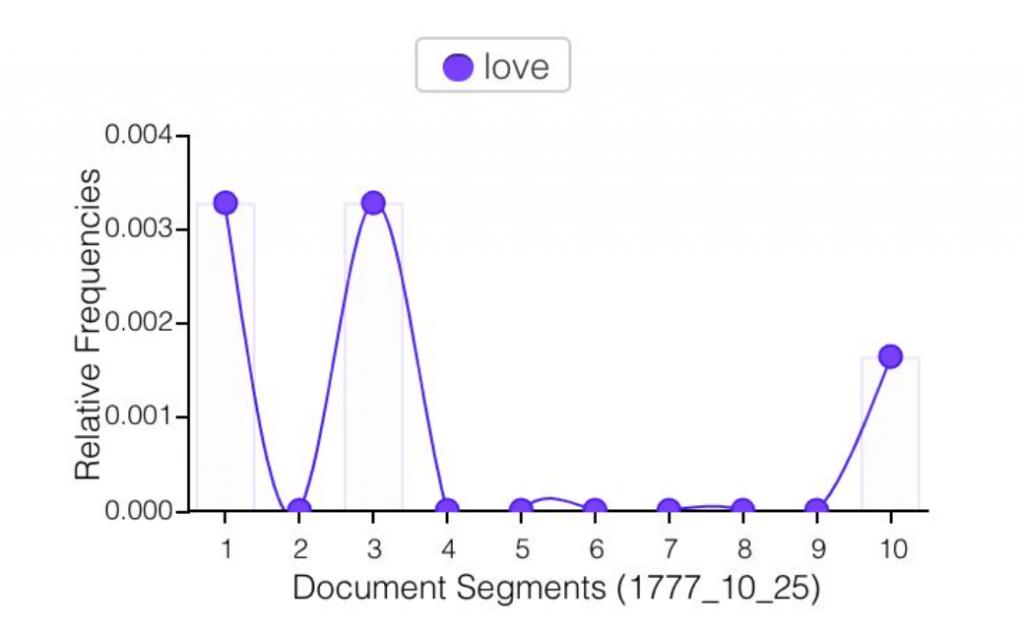

The primary, if not only, a way for Early American women to maintain relationships with their husbands was through the letter. Because of this, one of the primary methods of support women provided for their husbands was through emotional labor where women use certain language in order to tackle their everyday circumstances, such as the use of optimistic language. Despite whatever hardships these individuals faced, letters contained warm words. This is evidenced by the number of occurrences of words like “love” (37), “wish” (19), and “believe” (19). These words of hope and affection activate instances of intimacy between long-distance lovers. Using the Links tool (Fig. 4) I was able to identify colocates for these words, which included more words of a similar tone including “happiness”, “affection”, and “welfare” as shown in the image below. The proliferation of positivity was essential not only for maintaining relationships but also for encouraging husbands to continue their work in order to ensure the overall welfare of families. While these women lived independently without their husbands, they still relied on their financial support to preserve their wellbeing in their current and future homes. Women must perform this role due to their institutionalized economic dependency on a patriarchal figure; women’s subordination has been codified and enforced by the full power of the state since the inception of the state (Lerner 9).

Using the Trends tool (Fig. 5), we can also challenge my hypothesis. By identifying the location of each of these optimistic words, we can see in a letter from Lucy Knox to her husband (Letter from Lucy Knox to Henry Knox, 10/25/1777) that “love” takes place at the beginning and the end of her letter, suggesting that perhaps these words were forms of cordiality instead of words of pure encouragement. However, it can also be said that women’s love and affection manifesting as repeated, formal greetings is the reification of emotional labor. Perhaps, the rote use of optimistic language was a way for individuals to placate their partners even in the face of despair.

Figure 3

HEROINE, LOVE, FEAR, MIND, and BODY

The letters from Lucy Knox to Henry Knox show a mix of complicated words such as “love,” “fear,” “mind” and “body” that display the way in which early American women, such as Lucy, thought about themselves and the way they viewed their husbands’ roles. As seen in the “Links” tab of Voyant Tools, the word “love” is correlated with the word “attention” and “accompany.” The affiliation of these three words suggests that “love” may be used as a way to tamely plea for assistance. This idea is evident when Lucy writes to her husband, “My dearest only love – Where is my love in this day of general joy – were I assumed that he was well I should more sensibly partake the happiness of those around me – but in the present wretched uncertain state of things, at this cruel distance, and at this time of danger, I fear to…”(Lucy Knox to Henry Knox, 10/25/1777). Here, Lucy is using the joyous language of being in “love” when writing to her husband where she switches the tone from light to dark in order to inform him about the “cruel danger” she faces. She seems to use the word “love” as a tactic to bring attention to the “fear” she feels in her current environment, which suggests that she may not have felt comfortable complaining to him without first complimenting him. The need to balance the word “fear” with the word “love” implies that women believed that their tones should characterize warmth and submissiveness. By looking at the “Context” and “Links” feature in Voyant Tools, we can see that Lucy uses the word “love” in order to gain “attention” from her husband so that he can be aware of her “fears,” which suggest that she hopes to gain aid from him in times of fear.

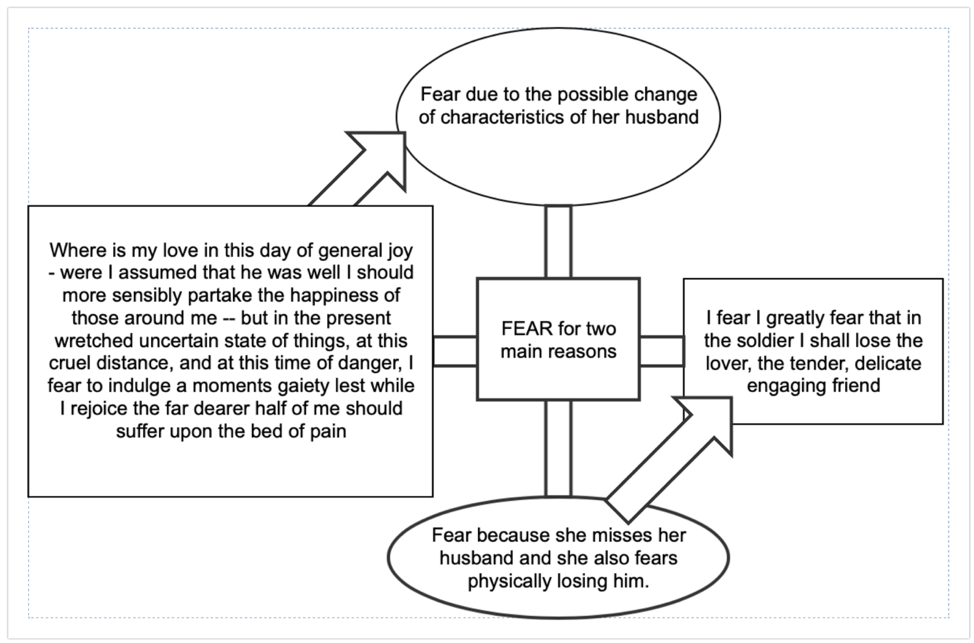

The idea of women viewing themselves as the submissive gender and therefore needing assistance from men is further illustrated when Lucy uses words such as “mind” and “body.” She says, “but I will endeavor to act the heroine –and if I fail remember I am weak in body as well as mind [then] let me hear from [and] believe never was an affection more pure or more ardent” (Lucy Knox to Henry Knox, 04/07/1780). In Voyant Tools, we can see that the words “mind”and “body” is linked to the word “let,” which suggests that she must first ask him for his permission as she believes herself to be the weaker vessel. Furthermore, this notion implies that women must always ask for approval from their patriarchal leader because of the ideology that women are inferior to men by having a fragile “mind,” and “body,” which leads them to not trust themselves. While Lucy doubts her own judgement, she trusts her husband’s ability to tackle many tasks simultaneously as she states that he is able to put his mind towards “many cares” (Lucy Knox to Henry Knox, 04/07/1780). Below is a visualization that shows Lucy’s language of fear is mainly due to two reasons: 1) the absence of her husband and 2) the idea that her husband may change due to the war:

Perhaps due to current social mores or biblical values, or both, a wife’s submissiveness was not uncommon in the historical moment in which these letters were written. For this reason, a woman’s self-image in this time period was subordinate to her male counterparts. This is illustrated in the usage of the word “heroine” as well as its collocates “endeavor”, “act”, and “fail” (Fig. 6). Using the Reader tool, I was also able to read the entire sentence and identify the words “weak” and “fail” to further contextualize the usage of “heroine” (Fig. 7). She writes: “I am sorry to be an addition to the many cares you must have upon your mind – but I will endeavor to act the heroine – and if I fail remember I am weak in body as well as mind.” The juxtaposition of “heroine” with “weak” and “fail” evoke a stark contrast, one that is telling of the writer’s negative self-image as well as the high expectations she has created for herself.

Looking at the term “know,” brings up similar concerns. By looking at the Document Terms tool we can tell that “know” is one of the most frequently used words (3 occurrences) in the corpus (Fig. 8). Because of this, we can assume that the word is important, or at the very least, its repetition bears emphasis. In another letter, Lucy Knox writes: As previously stated, the word “know” only appears in relation to “you”, meaning her husband, Henry Knox (Fig. 9). Through this evidence, I would like to posit that women deferred to men in every aspect of their lives, including their own self-image to heighten their husbands’ self-esteem. Subsequently the confidence men gained from women’s submissiveness would encourage them to support and provide for their seemingly “helpless” wives.

The daughter of a fiercely Loyalist family, Lucy Knox was abandoned by her family upon the start of the American Revolution (Hamilton 2). Married for less than a year, Henry and Lucy were only 24 and 18, respectively, at the battle of Lexington and Concord (Ibid.). Lucy’s young age coupled with a lack of family and often absent husband perhaps lend to both her tenacity and dependence on her husband. The letters between Lucy and Henry offer an alternative perspective to the American Revolution, allowing readers an understanding of the couple’s private sentiments and affinities in contrast to their public, historical depiction.

While Lucy displays herself to be a submissive wife, she also refers to her husband as a “tender, delicate engaging friend” (Lucy Knox to Henry Knox, 10/25/1777). These description associates Henry as an affectionate husband and depicts that he was referred to in a way that was rarely linked masculinity in early America. Lucy’s use of these words implies that her and Henry had a marriage that arose from a form of friendship. According to The Revolutionary Lives and Letters of Lucy and Henry Knox by Philip Hamilton, Lucy Flucker and Henry Knox experienced a “passionate courtship” that started at a coffeehouse near Knox’s bookstore, where they flirted with each other. The book states that Lucy was attracted to Henry’s physical built and their relationship filled with excitement and longing (9). However, Lucy’s friends and family opposed the marriage as Henry was a “son of a bankrupt mariner” (10). Knox was also perceived to have sympathies for the Whig party, whereas the policies of Lucy’s father was tied closely to the ministry in London. No matter, Lucy and Henry married, which cost Lucy her parents as they did not visit her in their Cornhill home (11). The newlyweds created a domestic life for themselves by setting up “housekeeping in Kon’s rented townhouse in Cornhill, purchasing furniture and a number of other household items” (11). This idea not only shows that Lucy and Henry were in love but that they worked as a team, which was rare for early American marriages. However, Henry became increasingly worried that “the ministry in London was bent on tranny,” which eventually led Henry to fight in the American Revolution (11, 31). Hamilton’s analysis gives us insight as to why Lucy was able to refer to her husband in as “tender” and “delicate;” she had a strong friendship as a foundation to her marriage, which gave her the freedom to use non-masculine adjectives when addressing her husband.

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Conclusion

The ideologies of womanhood in the early republic included their identity as one with their husbands’ needs. This is especially evident for women like the widow Mary Keating who lost her place in the world without a husband and had to seek support from another patriarchal figure. Stuck in Ireland, Keating wrote to Anthony in order to reunite with her native land in order to reclaim her American identity. Analyzing Keating’s letters with the works of Norton, Berkin, Lerner and Scott, it is made clear that there were many women like Keating who craved support but were rarely given any. In fact, many women were responsible for supporting their men in ways such as the use of optimistic language and the embodiment of patriotism. Lucy Knox’s letters to her husband shows that early American women were not only limited by men but they were also restricted by their own ideologies about womanhood. However, as these letters were written during the American Revolution, women had to also support men. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that even though these letters show submissiveness, Lucy is still willing to take charge at the absence of her husband and play a part in the war by supporting the soldiers. Support for men also included domestic roles like taking care of the children and the animals. Interestingly, the letters between Lucy and her husband also illuminates the role of Indian women who were known for their agrarian skills that not only included native crops but European crops as well. Hamilton’s analysis of Lucy and Henry Knox shows that Lucy and Henry had a courted romance, which made it possible for them to have a strong friendship in their marriage. This attachment meant that Lucy was able to confide in her husband and refer to him in a less “masuline” way by calling him her tender, friend as previously mentioned. Nevertheless, Lucy was still tied to the patriarchal society in the early republic, which meant that her independence was limited like that of other women in her society. Although women gained some independence during the American Revolution by taking part in political discourse and activism, a lot of women lost their autonomy by being imprisoned in their own homes while the soldiers raped or threatened them. Nevertheless, many women withstood their pain and triumphed.